There are a great many human inventions that encourage interpersonal connections and the exchange of goods and ideas in record time. Few, however, do it with the charm and romanticism of railways.

The iron horse, as the Native Americans called it, continues to be a symbol of progress and a key link for all cultures around the world.

This ABGstories recounts its history at full speed.

Putting ideas on track

Some of Western society’s most archaic tracks were laid in Greece. Thanks to diolkos (grooves dug in the trackway), Hellenic boats were able to cross the Isthmus of Corinth by land.

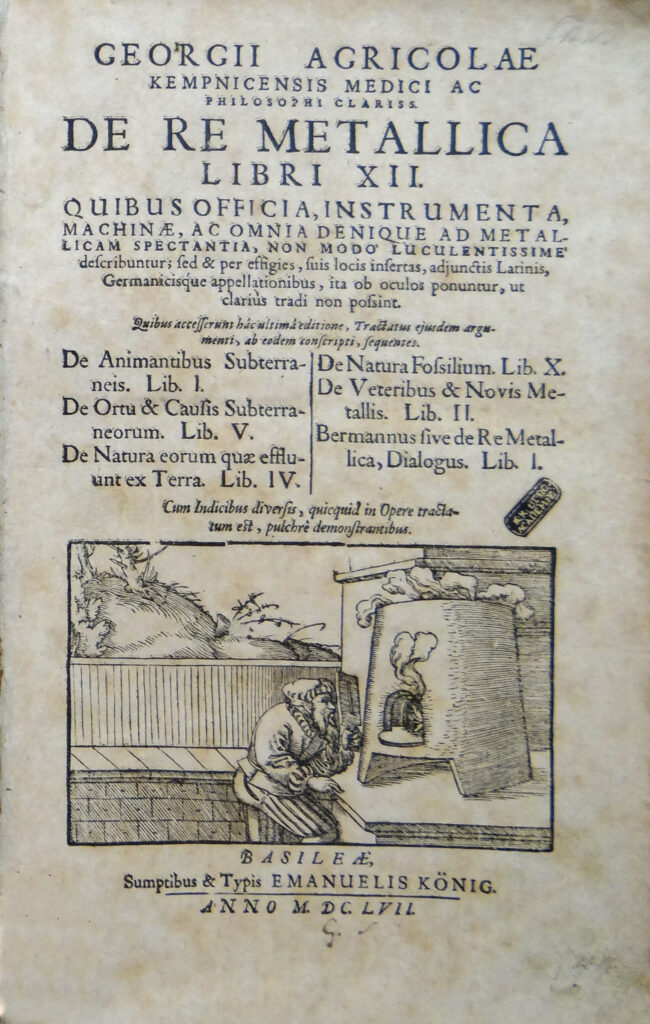

Moreover, trains have multicultural roots, as is well demonstrated by the 16th-century German wagons. The exploitation of Central European mines at the time highlighted the need for faster, more comfortable and more efficient means of transport compared to human chains in order to transport minerals abroad.

Chemist Georgius Agricola (born Georg Bauer in Germany) illustrated those wagons, which were animal-drawn and could move forward on wooden rails, in his work De Re Metallica (On Metals). The book marked a before and after in mineralogy and metallurgy.

Patents all aboard!

Let’s travel across the map and through time. From Germany to Spain. And from the 16th to the 17th century.

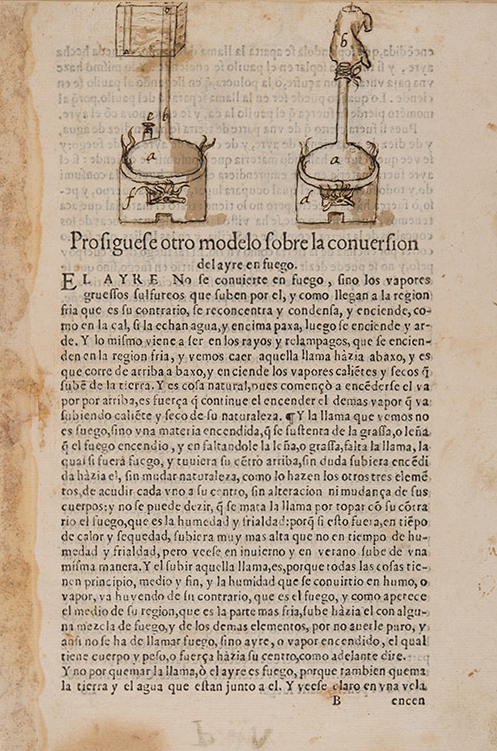

When patents still went by the name of invention privileges back in the 1600s, engineer Jerónimo de Ayanz amazed the court of Philip III with his ideas about using steam energy with different kinds of mechanisms. These ideas were, indeed, the first vestiges of the steam engine, many years before the Industrial Revolution took place.

In 1606, this pioneer saw how his 48 inventions were collected in a single invention privilege.

Next stop: England. In 1767, the breakthroughs developed by Richard Reynolds changed the transportation of goods. Cast iron replaced wood for the first time and became the star metal in the manufacture of rails and wheels.

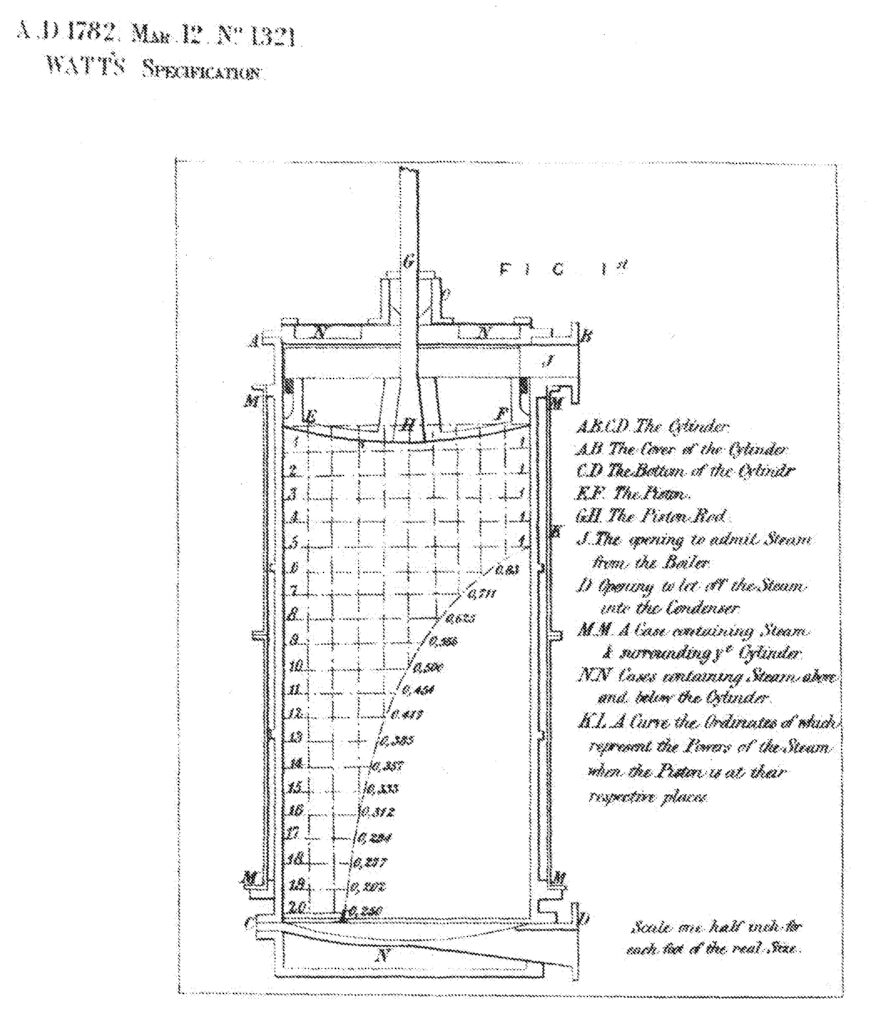

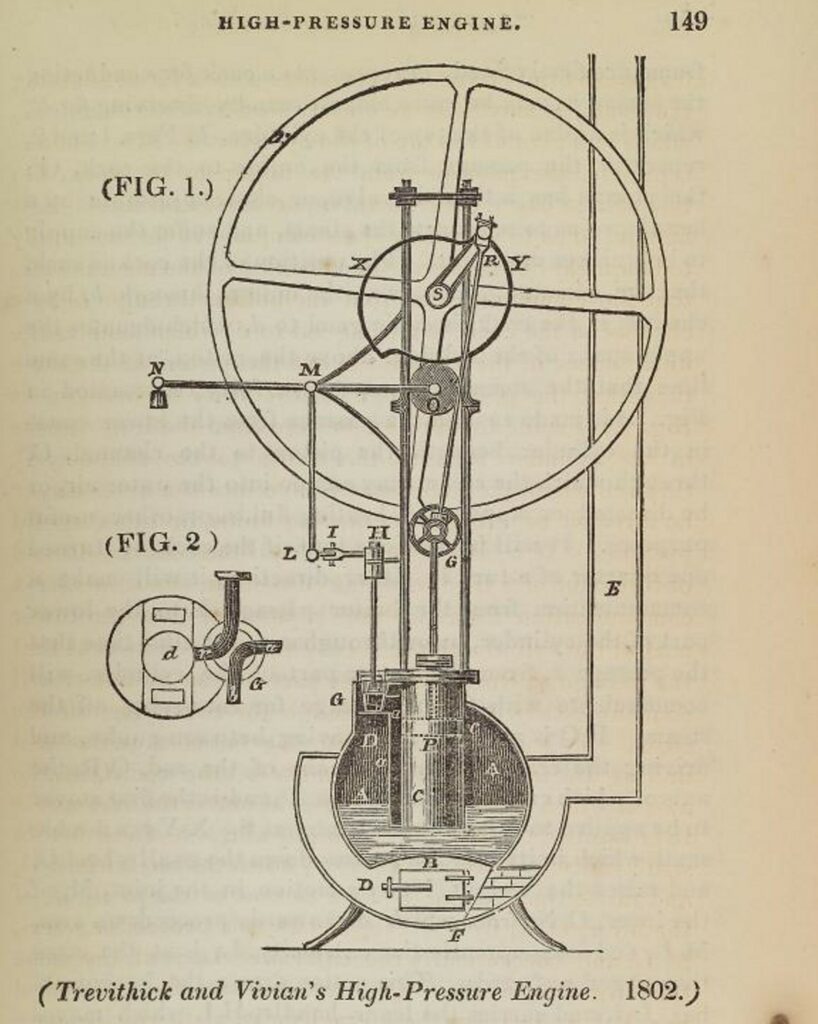

Several engineers contributed to making the train an invention of shared parentage during the years of the Industrial Revolution. Of these engineers, the ones most remembered by history are Scotsman James Watt and Englishmen Richard Trevithick and George Stephenson.

The former is credited with building the first British steam engine, patented in the first decade of the 18th century (GB 178201321). The engine’s great efficiency made it the industry’s most used machine at the time, thus relegating previous efforts by colleagues such as Thomas Savory to the shadows. Jimmy, as we would fondly call him, was also a pioneer in the use of centrifugal governors for trains.

The mechanism that made it possible to adjust steam flow so that the machine could automatically maintain a constant speed had its origins in the countryside. Dutchman Christiaan Huygens already used them in windmills during the 17th century.

When Watt’s steam engine patent expired in 1800, Trevithick was free to operate, develop and register (with the help of his cousin Andrew Vivian) a high-pressure steam engine in 1802. For his part, Stephenson first dabbled in this area in 1815 when he applied for a patent for one of his first engines. One year later, he would do the same for his suspension system with shock absorbers for the engine and iron wheels.

The choo choo trains that Trevithick and Stephenson played with led to history’s first locomotives and the first railway companies. The world’s first circulating train line was established between the British towns of Stockton and Darlington in 1825. Stephenson’s company, aptly named Robert Stephenson & Company, was behind that debut on rails. Shortly after, the English engineer took his developments to the mainland.

Steam locomotives were key to global land transportation during the 19th century and the early years of the 20th century. In countries such as Spain, several models remained in use until 1975.

Iberian width

It was year 1837 when the first train line was created in Spanish territory. Cuba, then a province of the Spanish Kingdom, was the chosen location and connected the towns of Havana and Güines. The peninsular equivalent arrived in 1848, with the line that linked Barcelona and Mataró.

Historical texts place Spain’s first railway patent application in 1845, registered under the name of Francisco Sánchez del Pando.

Although no documents of it exist today, the SPTO historical search engine does allow us access to the bibliographic data.

To get around the peculiarities of our land, achieve increased traffic of larger machinery on the rails and, above all, prevent the French from steaming ahead and invading us again, the first peninsular convoys began circulating on tracks with a width that differed from the tracks used in the rest of Europe. The measurement of 1,672 mm was standardised in the General Law on Iron Routes of 5 June 1855.

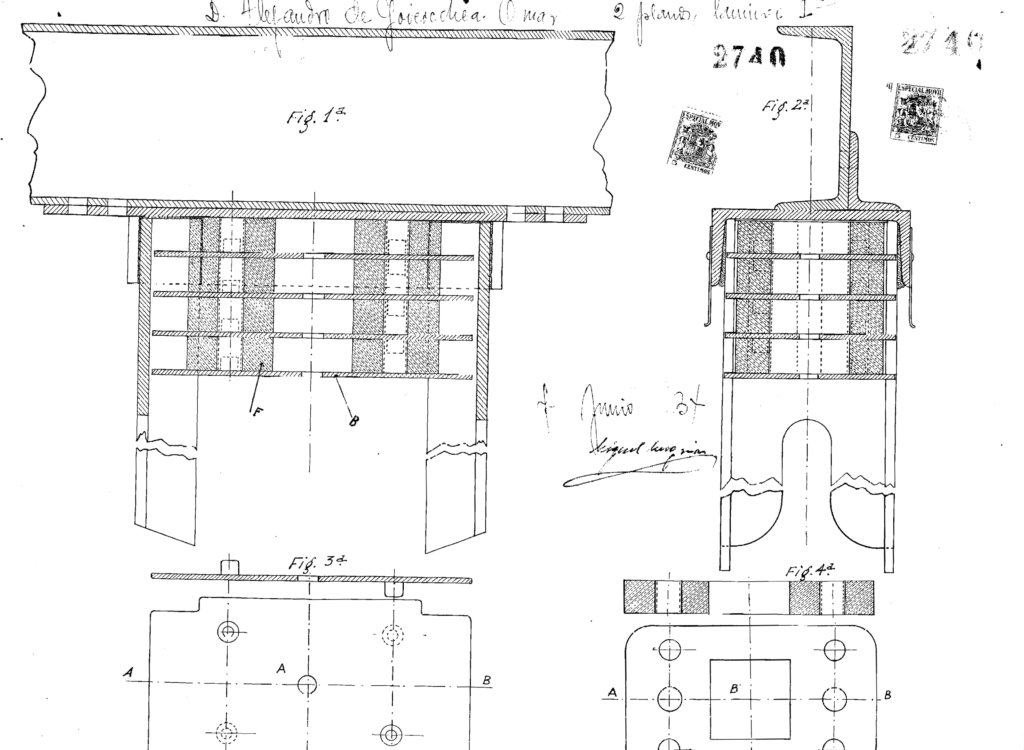

Moving on into the 20th century, there were two Spanish engineers who especially stood out in the sector: Alejandro de Goicoechea and José Luis de Oriol. Together they created Talgo (acronym in Spanish for Goicoechea Oriol Light Articulated Train), a true symbol whose first patent ES 103453 dates from 1927.

Years after its birth, the Talgo (and the rest of the Spanish iron horses) rolled along the “Iberian width”, the result of a new combination of Castilian and Portuguese measurements that increased the standard to 1,688 mm.

High speed

From the very first moment the train burst onto the scene as a means of transport, one of the main obsessions of engineers and inventors was to increase speed to shorten the duration of journeys.

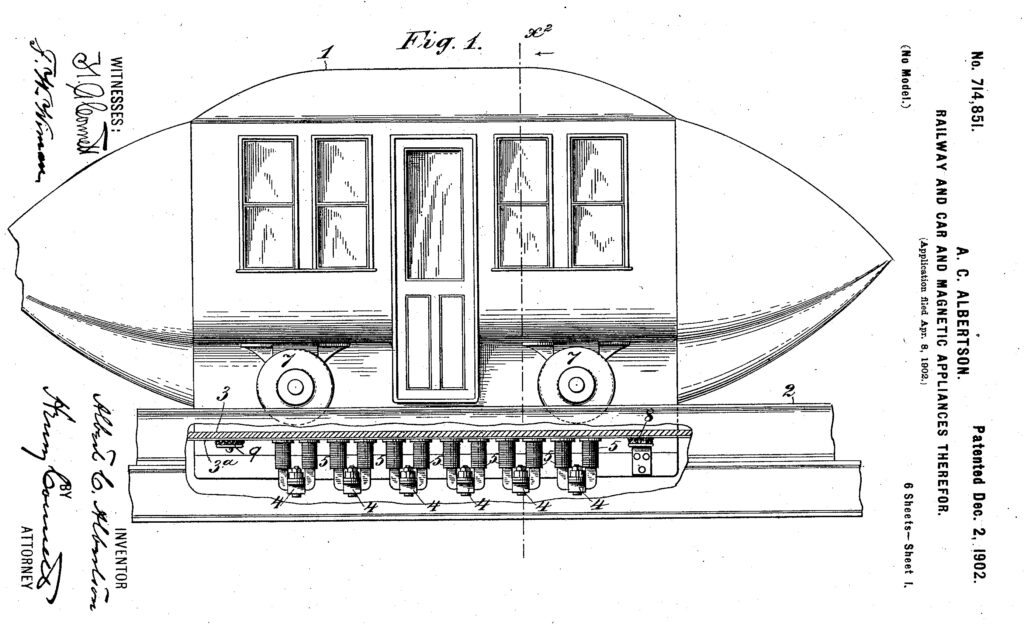

Despite its recent boom, high speed began to take off in 1902, the year in which Albert C. Albertson was granted a patent for his magnetic levitation project that took weight off the wheels and used conventional propulsion (US 714851).

This registration is regarded as the seed of Maglev trains (combination of the words “magnetic” and “levitation”). Suspension by magnets serves as the basis for the trains of the future, which are estimated to be able to reach 800km/h.

Last stop

We arrive at the last station of this ABGstories, remembering the traces left by the train’s rattling on intellectual property. There is something for all tastes and ages: older generations (El Consorcio), little ones (El Trenecito) and the forever young (ELO) at heart (Little Eva).

If you belong to arts and still have nightmares about maths problems such as “if a train leaves Barcelona at 8 am and another leaves Madrid at 9 am… at what kilometre will they meet?”… just liven up your trip by taking from the playbook of the master Agatha Christie.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the station masters Fernando Prieto, Sandra Ortuzar and Pablo Calvo for their review and input.

Jerónimo de Ayanz’s invention– National Library of Spain – Hispánica Digital Library, under license CC BY SA 4.0.