The fight against cancer has seen multiple glimmers of hope, but none of them have proved as promising as immunotherapy. Treatments that aim to boost immune defence restoration and reduce the side effects of more aggressive therapies have revolutionised research development.

Origins

Even though immunotherapy has been coveted by scientists during the past several decades, this does not mean it is the latest trend in medicine. In the mid-1860s, two German doctors, Friedrich Fehleisen and Wilhelm Busch, carried out the first comprehensive study of the immune system. Their research revealed the role of bacteria as anticancer agents after tumour regression in an organism that was infected with erysipelas (infectious skin disease that causes skin redness).

The German discovery was crucial for the work that William Coley would develop almost thirty years later. This American surgeon distanced himself from traditional inoculation with live bacteria, opting to prepare bacterial toxins in 1891 on his own. His formula mixed dead samples of the species Streptococcus pyogenes and Serratia marcescens. The experiment has been historically known as “Coley’s vaccine”, though it was never patented nor was its use standardised due to the lack of mass trials that are required to corroborate its effectiveness, high production cost and unfavourable side effects. Even so, the method earned Coley the title of “father of immunology”.

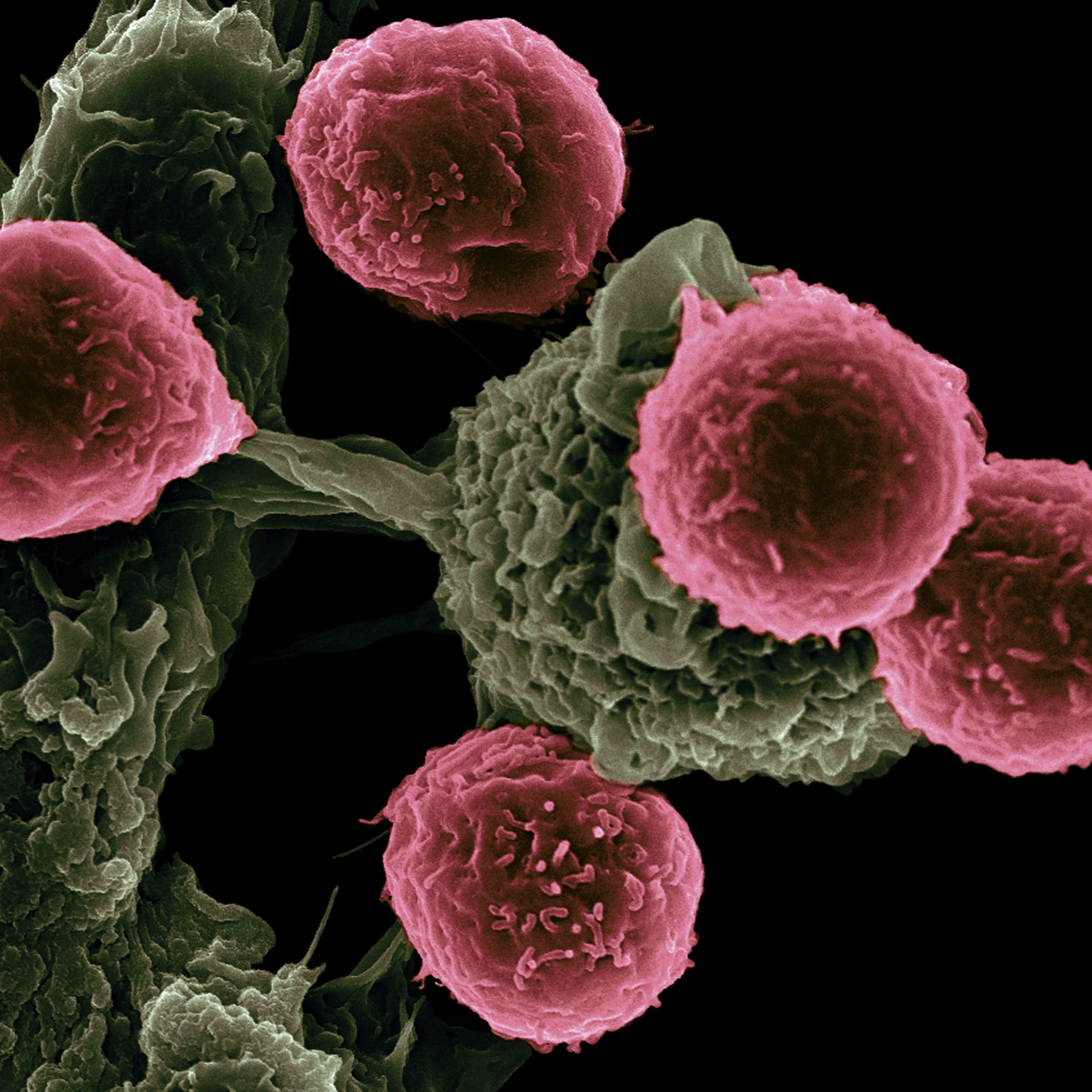

The consolidation of radiotherapy as an exceptional cancer treatment in 1896 caused the advances of William Coley to fall into oblivion until 1967, when T cells were discovered. Since then, oncologists studied the functions of the immune system in greater depth, focussing on understanding how such system recognised cancer. In practice, cytokines, which are proteins generated by cells that activate immune action, started to be analysed separately.

Two men, one fate

During the 80s, James Allison from the US and Tasuku Honjo from Japan cemented their respective anti-cancer trajectories. This is how the events unfolded in the lead-up to their shared 2018 Nobel Prize in Medicine for the discovery of cancer therapy by inhibition of negative immune regulation.

Tasuku Honjo identified and cloned the cytokines IL-4 and IL-5 and discovered the AICDA enzyme which, in addition to creating DNA mutations, influences the biological mechanism of antibody production (the so-called Class-Switch Recombination) and somatic hypermutation, by which the immune system adapts and reacts to the presence of foreign elements.

In 1982, Allison already knew that the immune system’s inability to attack cancer cells was due to the association of antigens produced by those cancer cells with additional T cell proteins. That same year, he researched the mechanisms and structure of said additional proteins: the T-cell antigen receptors.

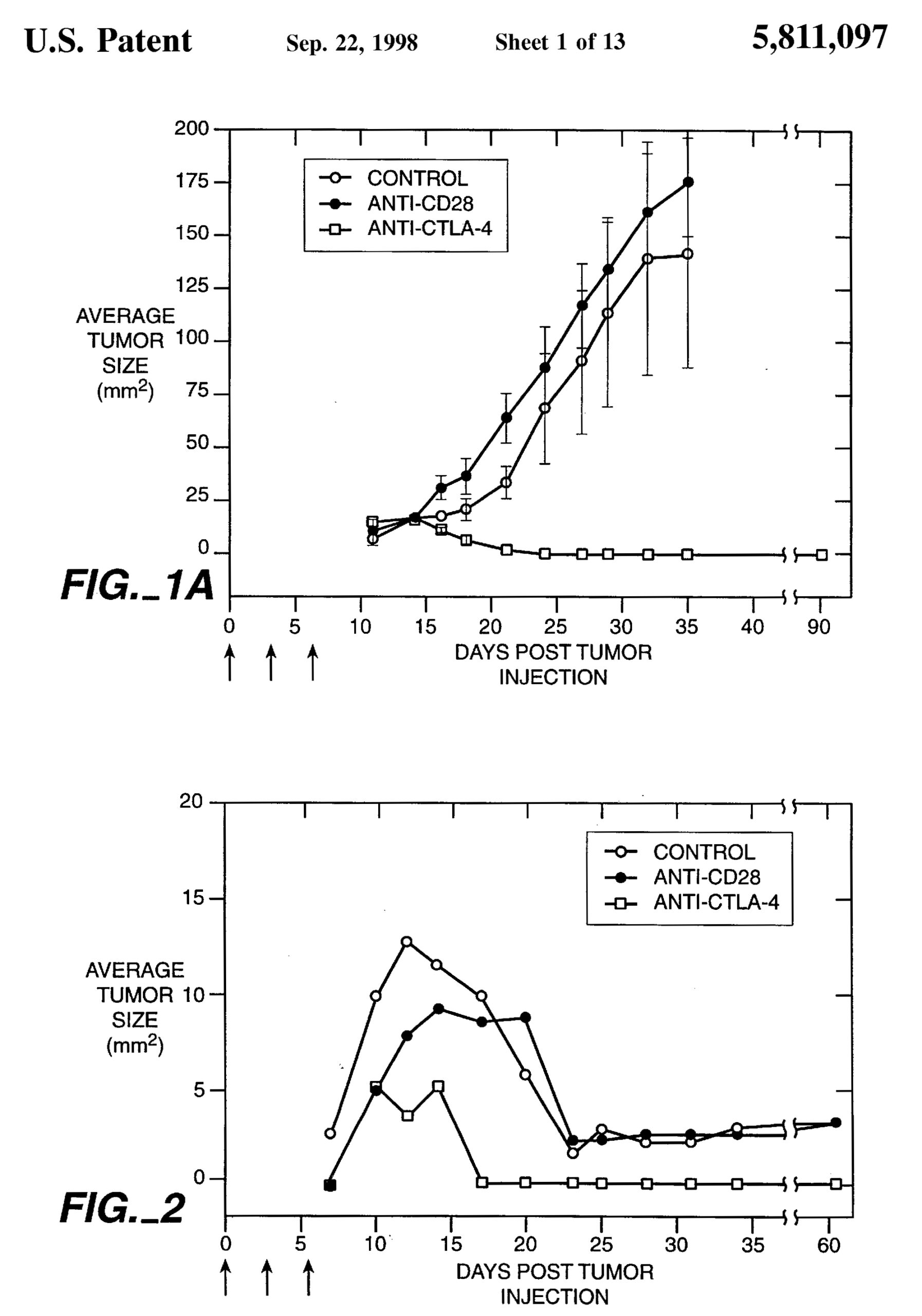

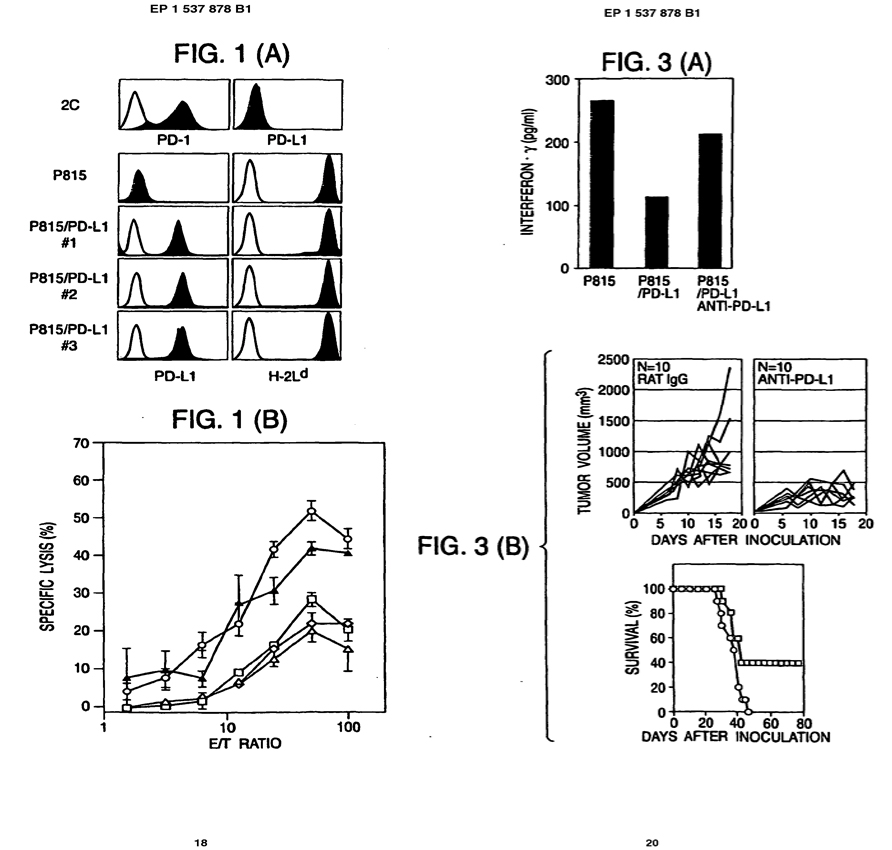

The 90s arrived and Allison found the CTLA-4 protein on the surface of T cells. Honjo, on his part, discovered the PD-1 protein (or programmed cell death protein 1 together with its activating ligand PD-L1) that shared location and biological effect with CTLA-4, although with a different mechanism. Both scientists concurred in their verdict: both CTLA-4 and PD-1 must be blocked so that T cells can recognise and kill tumours and the immune system can function at its full potential.

Patents, costs, licences, infringements and other breaches

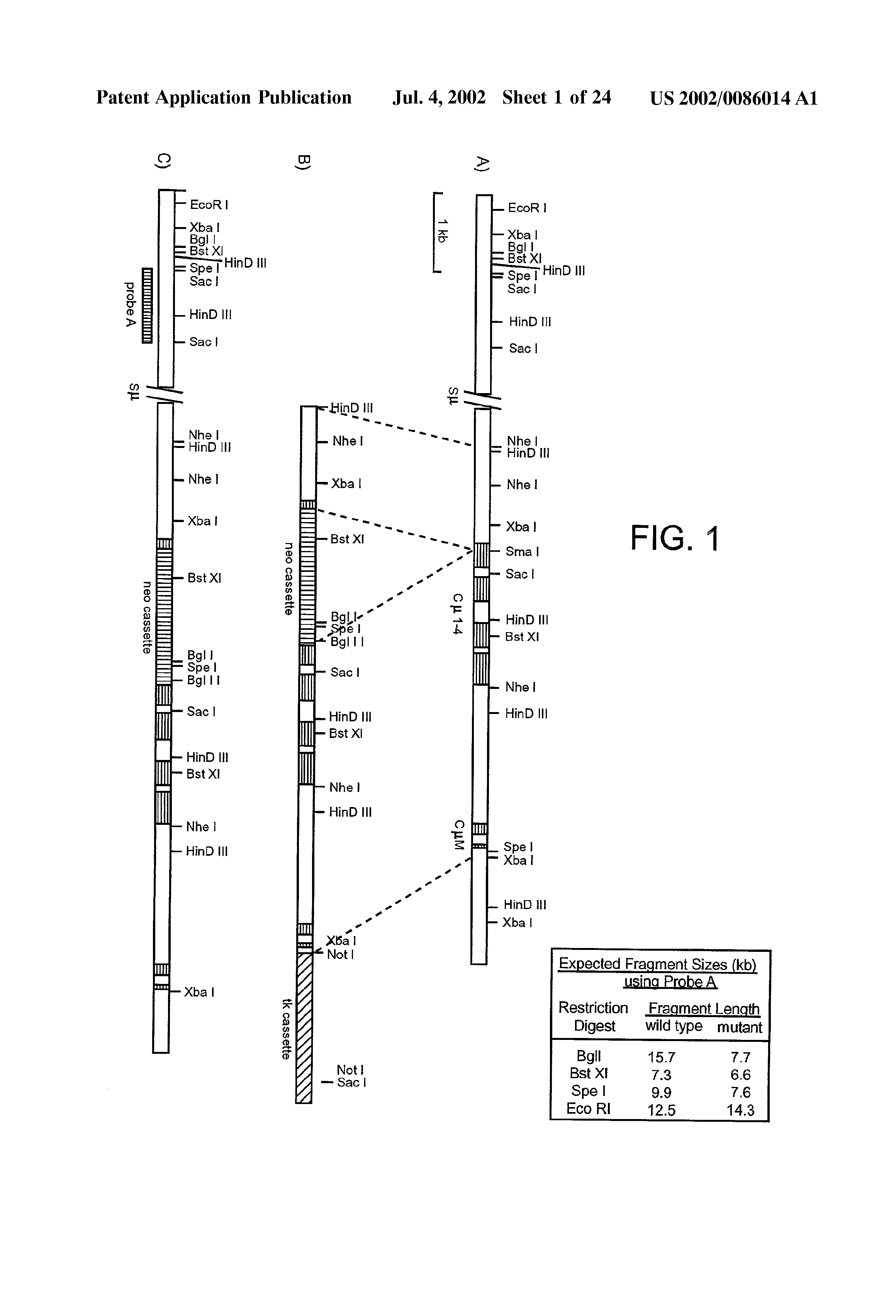

In the mid-90s, Allison patented his blocking technique, with the University of California as the applicant and himself as the inventor (US5811097), and he began to seek support to develop a drug.

Since the University only had the expertise to research the preclinical stage, they authorised the use to NeXstar Pharmaceuticals in 1998. Shortly after, the small biotechnology company was acquired by Gilead Sciences Inc., which was responsible for sublicencing the rights to the biopharmaceutical company Medarex.

With the arrival of the new millennium, Allison saw many years of research materialise in the ipilimumab drug.

In 2004, Medarex partnered with Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) to work on development and marketing.

The approval for use in adult patients came about in 2011, under the trademark Yervoy® (US 8017114B2).

Tasuku Honjo entered the 21st century in partnership with the Japanese company ONO Pharmaceuticals, patenting the use of the anti-PD1 antibody in the manufacture of drugs for treating cancer and other infections (EP 1537878B1) in 2003. It was then that ONO Pharma signed a licence agreement with BMS that allowed for the creation and commercialisation of nivolumab (under the brand Opdivo®) to fight various types of cancer.

The grant of an American patent (US 8728474B2) with an effective filing date of 2003 addressed to Opdivo and that, broadly speaking, covered the use of an anti-PD1 monoclonal antibody against a tumour sparked war between pharmaceutical giants. Merck & Co., responsible for the invention of pembrolizumab (Keytruda) in 2006 for treating melanoma, strongly objected. Keytruda is specifically an anti-PD1 monoclonal antibody. Thanks to some swift trials, Merck’s antibody was given the green light in the US in September 2014, three months before Opdivo.

ONO and BMS counterattacked. Merck & Co. was sued for patent infringement in Europe, Japan and Australia between 2014 and 2016. The conflict was finally settled with an agreement between the parties. Merck agreed to pay the plaintiffs US$625 million and a portion of the revenue that would be generated by the sale of Keytruda from 2017 to 2026. On the other hand, ONO and BMS agreed to end all patent infringement lawsuits against Merck’s sale of Keytruda worldwide.

Technical tie, billionaire earnings

In the midst of award hangover, legal squabbles returned to the forefront. Tasuku Honjo announced his intention to sue ONO Pharmaceuticals in 2019 after learning about the ludicrous royalty percentage that the company intended to offer him as an inventor: a meagre 1% (when the usual ranges between 5% and 6%).

By doing so, Dr. Honjo followed in the footsteps of his fellow countryman, Shuji Nakamura, inventor of the first high-brightness blue light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and violet lasers (JP 2628404) and winner of the 2014 Nobel Prize in Physics. The engineer sued his former company, Nichia Corp., for unfair compensation, and they ended up agreeing to a payment of 9 million dollars.

Tasuku Honjo’s legal battle ended in November 2021 with billionaire figures. The Japanese scientist got ONO to pay him 5 billion yen (about 44 million dollars) and, on top of that, to donate another 128 billion to a foundation belonging to Kyoto University that supports young researchers.

The legal comings and goings of these big names should make us aware of how essential it is to seek impartial advice before assigning IP rights, as well as specifying the role and rights of each party involved in a collaborative project.

Back to the scientific area, despite the ray of hope that the work of both immunologists sheds for the future, even now in 2022 there are two relevant hindrances that prevent progress from swiftly advancing: high drug production costs and insufficient profit reinvestment in R&D.

Even so, nobody can deny that immunotherapy is on the right track to reduce the incidence of cancer in our society to a minimum.

Recommended videos:

James Allison’s 2018 Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech

Tasuku Honjo’s 2018 Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech

Acknowledgments

Thanks to my colleagues Agustin Alconada, Hélio A. Roque and Iain McGeoch for their reviews and input during the writing of this text, which was promoted by our co-founding partner, Francisco Bernardo (R.I.P.).