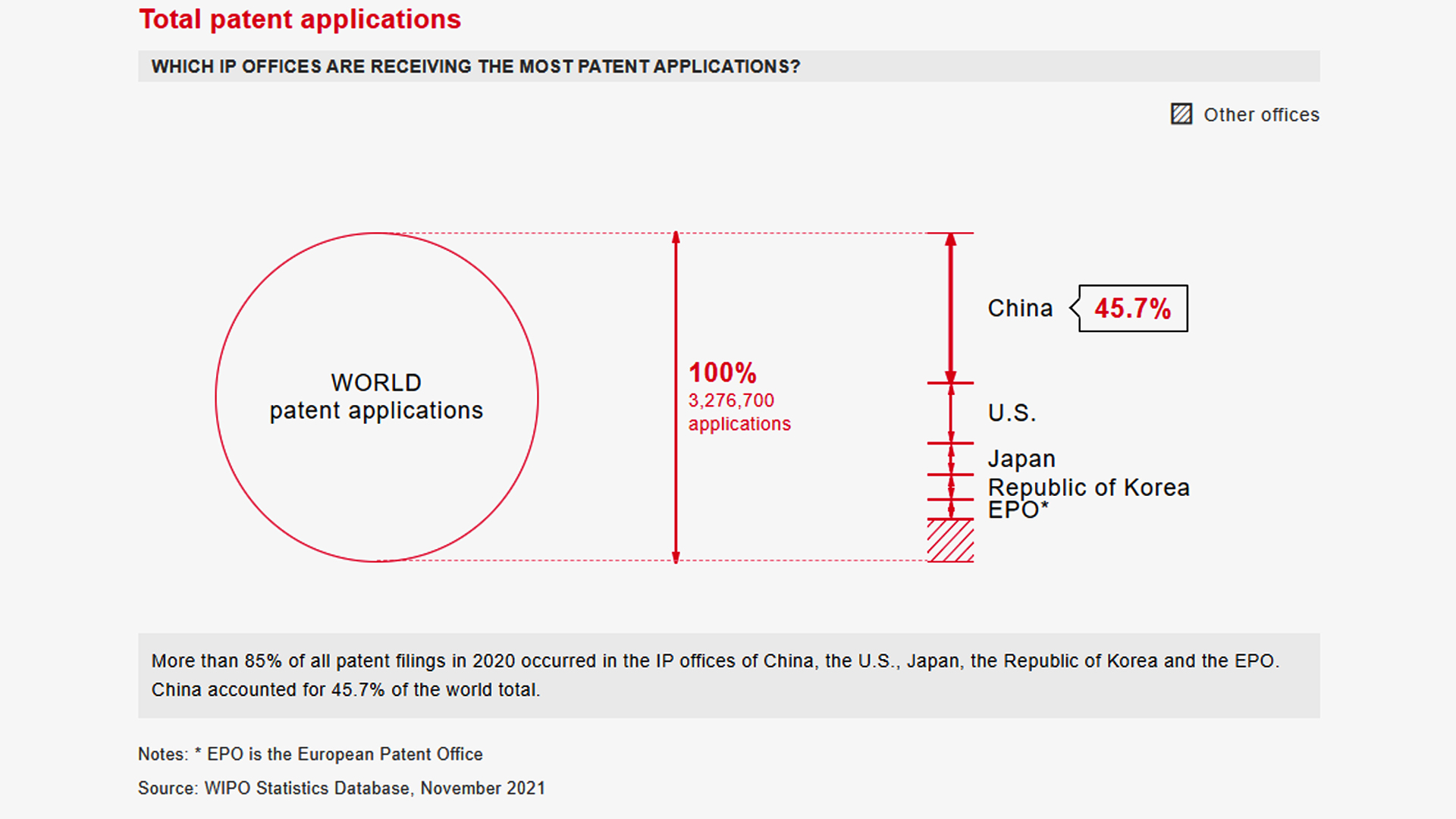

According to the latest data published by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), in 2020 the Chinese Patent Office was the office that received the most patent applications in the world, with 45.7% of the total.

Obtaining exclusivity over the use of an invention in a market with millions of people is business reason alone to internationalise protection to China, but it is not the only one. Today, the People’s Republic has already become one of the world leaders in R&D and international patent applications, which, together with its enormous production capacity, makes it a territory where industrial property (IP) must be protected from a strategic point of view.

In this article we explore the country’s patent system and analyse the many similarities and differences compared to what has been established in the West.

Patent protection in China: late, but quickly evolving

We cannot possibly speak about IP in China without briefly reviewing its history. the country’s first modern patent law entered into force in 1985, which is quite late if we compare it to other countries around the world. The main reason for such late regulation is that for many years prior to Deng Xiaoping’s opening up of China’s economy in 1978 – especially during the challenging years of the Cultural Revolution- inventions and the right to exploit them belonged to the State.

Despite the late entry into force of the first patent law, it has since evolved very quickly. In fact, to date the law has already been reformed four times. The most recent reform became effective on 1 June 2021, and will be discussed later in this article.

Other aspects of IP in China have also evolved at this same rate. For example, the first judicial body specialised in IP was created in Beijing in 2014. Today, only seven years later, this Asian country already has 18 courts and 4 tribunals specialised in IP and, most importantly, a chamber of the Supreme Court exclusively dedicated to IP. All this translates into administrative and judicial proceedings with much greater rigour and quality for companies that make use of the Chinese patent system.

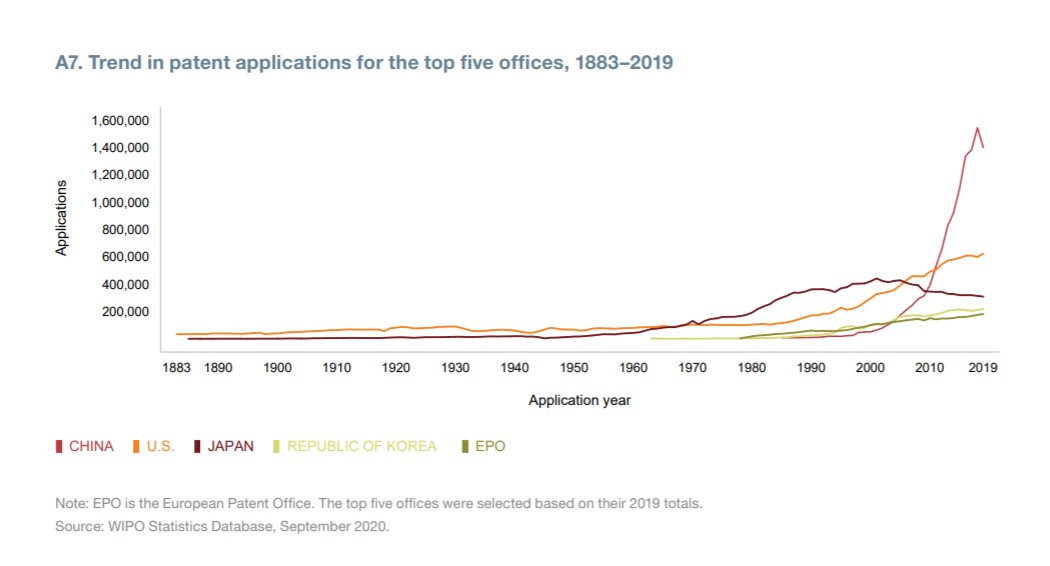

Another highly visual diagnostic indicator is the evolution of the number of patent applications in China: the 1.3 million applications in 2019 is quite striking compared to the 300,000 applications in 2010. China is also the largest user of the PCT system with 68,720 applications in 2020, well above the USA (59,230) and Japan (50,520).

As can be seen, in the last ten years patents have boomed in China and the country is already recognised as one of the top five patnet jurisdictions, along with the United States, Europe, Japan and Korea. China’s strong commitment to IP definitively breaks away from its questionable reputation of yesteryear.

Industrial property conventions and treaties

China is currently a signatory of the main patent agreements and treaties: the Paris Convention, the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) and the Budapest Treaty.

Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan

It should also be noted that Chinese patent applications, despite covering a market of more than one billion people, do not cover three areas of interest for their economic relevance:

- Hong Kong

- Macau

- Taiwan

Special care must be taken when seeking patent protection in Taiwan. Although Hong Kong and Macau can be accessed through a simple extension (administrative procedure) of the Chinese patent application, this application cannot be extended to Taiwan, with the added drawback that Taiwan is not a signatory of the PCT. Therefore, if the Taiwanese market is commercially attractive and there is a desire to protect technology there, such protection must be applied for in this country within 12 months from the filing of the priority application in the patent family (which is usually a Spanish or European application). For example, Taiwan is a world leader in the field of semiconductors.

Terms of protection for Chinese patents and utility models

The term of a patent in China is, like in most countries, 20 years from its date of appication.

However, after the entry into force on 1 June 2021 of the Fourth Amendment to the Law mentioned hereinabove, two mechanisms can be applied to extend said term of the patent:

- Patent Term Adjustment (PTA):this applies to any invention regardless of its technical field. This mechanism compensates the applicant for delays in the patent granting procedure that are caused by the Patent Office. Once applied for, the Office can add the days it deems appropriate to the standard 20 years.

- Patent Term Extension (PTE):this is the equivalent to Supplementary Protection Certificates in Europe (SPC, or Certificados Complementarios de Protección or CCP in Spain). It applies to certain pharmaceutical inventions and its purpose is to compensate for the loss in monopoly time over an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) on the market which is caused by delays in the issuance of its marketing authorisation. With this mechanism, protection of the API subject of the patent can be extended to a maximum of 5 years. The patent can be for a product, method or medical use related to the API, and it must be the first time that said API has received marketing authorisation in this Asian country.

In China, like in Spain, utility models are also available and their use is in fact very widespread. Utility Models also has a term of 10 years, do not cover methods and, as in Spain in the past, protect engineering, but not science.

Prosecution times

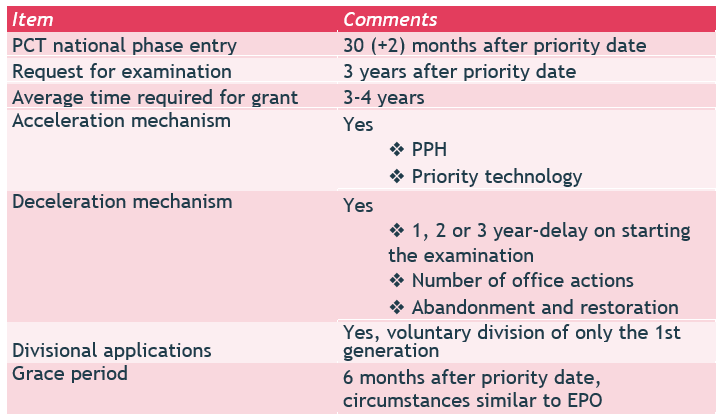

It is very important to keep prosecution times in mind so that an efficient strategy for protecting an invention can be implemented. The following table summarises key timeframes and deadlines in China.

There are two particular processing mechanisms in China that are not seen in other traditional jurisdictions, such as Europe or the United States, and that are worth noting.

The first is the possibility of extending the deadline to enter the Chinese national phase from 30 to 32 months after the priority date by paying a small administrative fee. Since a national phase entry involves a good number of administrative acts, including the filing of a Chinese translation of the patent text, this extension can be very helpful when a belated decision, due to business, financial, or other reasons, has been made to seek patent protection in China.

The second is the possibility of substantially slowing down prosecution in a cost-effective way. There are cases in which this can be an extremely valuable strategic tool, primarily when the applicant does not have high hopes that a patent can be granted. In such cases, the legal uncertainty that an unresolved patent application (i.e., one that has not been granted or rejected) affords is a significant deterrent for third parties, since said third parties will think twice before taking the invention subject of the patent application to the market until they have certain guarantees that the patent right will not be granted and, therefore, that it will not be infringed. If all the available deceleration mechanisms mentioned above are applied, the applicant can easily find themselves eight years after the priority date without the Chinese Patent Office having resolved the case.

Notable substantive patentability aspects in China

It is interesting to note here that the Chinese Patent Law, as far as its pre-grant practice is concerned, is modelled on the European Patent Convention. In fact, when the first patent law entered into force in the 80s, an agreement was also reached between the Chinese Office and the European Office according to which Chinese examiners could be trained at the European Patent Office. Some 2,000 Chinese examiners took advantage of this opportunity.

We can thus affirm that, in substantive terms, and especially in what relates to novelty and inventive step, European and Chinese practices are quite similar. Although somedifferences are noticeable in the area of science which will be discussed later, the similarities in technical fields with a greater focus on engineering are remarkable. On the other hand, the inventive step analysis follows a scheme that is practically the same as the European “problem-solution approach”, wherein the verdict on inventive step pivots on the technical effect discovered by the applicant (and not on a different technical motivation) i. In this regard, Chinese practice is closer to European practice than US practice.

Where a discrepancy between Chinese practice and European or US practice can be observed is in the extent of generalisation of protection permissible. As is known, one of the tasks that a patent attorney has when drafting an application is to claim, in a reasonably broad way, the specific discovery obtained in the laboratory by the applicant, to thus try to maximise the scope of protection conferred by the future patent. Depending on the country, the extent of generalisation that is considered to be reasonable varies, and in China it is lower than in Europe or the US. Therefore, it is not uncommon for the Chinese patent to cover less subject matter in one same patent family than the corresponding patents in the aforementioned Western jurisdictions.

Medical and diagnostic uses

As for medical and diagnostic uses, in China the so-called Swiss format is followed; in other words, protection can be obtained for the use of a pharmaceutical ingredient for the manufacture of a product for a specific medical use, and not for the medical use of the pharmaceutical ingredient.

Let’s imagine that ibuprofen is already known, but we discover that it can be used to treat diabetes. In China, this new use could be protected with a claim such as “use of ibuprofen in the manufacture of a medicament for the treatment of diabetes”.

Although medical uses are protected employing a different wording in Europe and the US, in essence the three jurisdictions allow protection for the use of a known drug to fight a new disease.

That being said, the situation changes when the invention lies not in treating a new disease, but rather in a so-called further medical use. We refer to a further medical when a certain compound and its use in a specific disease are already known, and the invention relates to some other aspect such as, for example, the group of patients to be treated, the dosage regimen or, even more frequently, the route of administration of the drug.

In Europe and the US, these inventions generally represent patentable subject matter, but in China a subtle difference must be brought into the equation: for inventions of this type to be patentable, they must affect the manufacturing process, which makes sense if we consider that this is ultimately what is being claimed.

This means that the final form of the product or medicament must be different to the know one. In the first two scenarios described above, it is likely that the drug itself administered with a new dosage regimen (e.g., three times a week) or to a new group or subgroup of patients (e.g., patients with a certain mutated gene) will not vary substantially with respect to the version of the drug previously used in the prior art. In these cases, it will not be possible to obtain a patent in China. In the third scenario referred to above, it is more likely that a patent can be obtained since the change in the route of administration (e.g., oral administration vs. inhalation) usually entails an alteration in the form of the medicament.

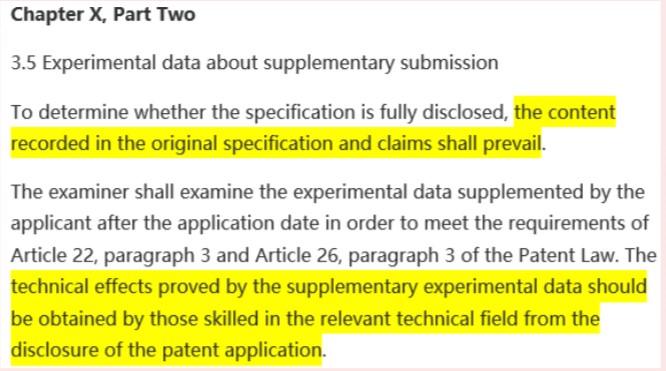

Provision of post-filing experimental data

It is common to provide experimental data obtained after the patent application has been filed to defend its grant, especially in the scientific field. This matter is so important that it was one of the main points discussed in the so-called Phase One Trade Agreement reached between China and the US just before the pandemic.

The reason for this is that in China, historically, such post-filing data were not accepted or were only accepted under very strict circumstances. Both China’s position – based on the obligation to be in possession of the patentable discovery and supporting evidence at the time of applying for a patent-, and Europe or the US’s position – which is more applicant-friendly -, are based on complex technical, legal and socio-political criteria that are beyond the scope of this article.

As a result of the aforementioned agreement between China and the US, in January 2021 the Chinese Examination Guidelines were amended and examiners were required to assess post-filing data relating to sufficiency of disclosure or inventive step. The wording of the Guidelines, however, cleverly gets around this obligation “imposed” by the Agreement and requires that the objective technical problem to which said new experimental data relates must be described very concisely in the original text. This requirement is, in practice, very difficult to fulfil because, at the time of filing the patent application, the applicant will not have been able to foresee this technical effect and, therefore, will not have been able to describe it in the original specification.

As a point of comparison, the European Examination Guidelines state that the objective technical problem to which the new experimental data relates must be implicit or related to the technical problem suggested in the patent text.

Returning to the previous example, let’s suppose that it is discovered that ibuprofen can be used to treat diabetes and the patent text only talks about this therapeutic effect. In China, it will be virtually impossible to achieve patentability through experimental data filed a posteriori which demonstrate the lower toxicity of ibuprofen compared to related drugs, since the original patent text did not mention toxicity. In Europe, it would be possible to base patentability on the lower toxicity, since it is understood that pharmaceutical activity and toxicity are aspects that a person skilled in the art would always analyse in the context of a new medical use.

Ultimately, our recommendations for patent protection in China remain the same as always:

- include all possible assays in the original patent text; and

- at the time of drafting the text of the application, provide your patent attorney with any indication of a technical advantage, offering as much detail as possible so that it can be reflected in the patent text.

Post-grant proceedings

Unlike in Europe, China does not offer independent patent office opposition and judicial invalidation proceedings, but rather everything is unified under one single invalidity procedure before the Re-Examination Panel of the Patent Office. This panel is an independent technical-judicial body, similar to the Board of Appeals of the European Patent Office. There is no time limit for starting the invalidity proceeding. The decision of invalidation is appealed before the Beijing IP Court, and ultimately before the Supreme Court.

Another interesting aspect is that, unlike in Europe, it is very difficult for a patent owner to limit the claims of the patent after the grant. The only way to limit these claims is after a third party initiates an invalidation action against the patent, but even then the claims are only amended if the amendment responds to an objection from the third party and only if it involves eliminating or combining claims.

Therefore, even in this scenario, there is very limited room for manoeuvre.

Regarding third party observations, they do exist in China, but only pre-grant. The grounds for objection, nevertheless, are not limited to certain pre-established patentability requirements like in other countries; instead, they can be brought against any aspect of the law that the third party believes is being violated.

Concerning infringement actions, the Chinese system offers a very interesting strategic duality. Specifically, said actions can be initiated either by an administrative procedure (before the State Administration for Market Regulation or SAMR) or through the Courts. The administrative route is attractive in that the cessation of the infringing activity can be achieved quickly (normally within months) and also cheaply, although compensation for damages must be claimed through the courts.

Enforcing Chinese patents: is it hard to do?

We can certainly say that infringement of third-party patent rights was inexpensive in the past in China. However, in recent years the possibilities of enforcing Chinese patents have become similar to those of other Western jurisdictions.

For instance, damages awarded by Chinese courts for the infringement of IP rights have grown exponentially in the last ten years, especially after the Fourth Amendment to the Law.

Historically, there has also been a prejudice that Chinese courts are protectionist. However, studies from various Western universities conclude the opposite, providing data showing that, in the last decade, foreign plaintiffs are more successful in obtaining an infringement decision than local plaintiffs, and that the former obtain compensation on average three times higher than that awarded to the latter.

We believe that all the above helps overcoming the idea of old that applying for a Chinese patent is a waste of time because of the difficulty in enforcing it. The truth is that China is no longer a country that copies ideas, but rather a country that strives to be at the forefront of innovation. The country knows that it is not possible to achieve international recognition in this regard without a solid IP system.

In short, taking into account the meteoric evolution of the Chinese patent system in the last decade, applying for a patent in this country has become essential in most technological sectors.